The Strange Story of Dina Sanichar, the Boy Raised by Wolves

Brent Swancer September 11, 2021

What makes us human? Are we born this way, or are we shaped and molded into what we are by society, with our own animal instincts subdued by our social mores? Indeed what happens when we strip away that touch of civilization and human upbringing? Throughout history have come tales of mysterious people who may shed light on the answers to these questions, in the form of what have come to be called feral humans. These are people who for whatever reason have grown up without human contact, in some cases raised by wild animals, and seem to have shed many of the hallmarks of what we consider to be “human.” In the absence of the influence of civilization they seem to have crossed over that barrier that we like to think separates us from wild animals, and in the process have become in a sense wild animals themselves. One of the more well-known cases of a feral child comes to us from India, and it is a case that offers an intriguing glimpse into the life of a person who was raised outside of the world of humans and our parameters for civilization, as well as a look at what perhaps makes us human.

In February of 1867, a group of hunters was making its way through the thick jungle of cave in Bulandshahr, Uttar Pradesh, India when they spied a pack of wolves entering a cave up ahead. Seeing as how the region had been beset with wolf attacks at the time, the hunters saw this as a chance to exterminate some of the vicious creatures. They formulated a plan in which they would set fires at the mouth of the wolves’ cave den and smoke them out. They did this, and before long the wolves came running out into the open, where they were picked off one by one by the armed men. Just as they thought they had killed all of the creatures, the sound of another was heard coughing and scrambling about in the gloom of the cave, but when a shape bloomed out of the darkness, they were just barely able to hold back their gunfire when they realized that this was no wolf. What came scampering out of the murky depths of the cave into the open was a young human boy, no older than 6, running about on all fours and snarling in a bestial manner at the hunters. So would begin the rather strange story of Dina Sanichar, the “Wolf Boy.”

At first the boy could not be approached, as he was every bit as vicious as the wolves that had been slain. He snapped and bit at anyone who would come near him, and he was only able to be gathered up when he ran out of energy to slump down by one of the dead wolves and bury his face in its fur as if in mourning. Even then, the boy put up a fight, but now they were able to subdue him and bring him to the Sikandra Mission Orphanage, in the city of Agra, where he was named Dina Sanichar, with “Sanichar” the local word for “Sunday” as that was the day on which he was brought in. They put him into a room but he would prove to be far from an ordinary boy. Not only did he nimbly walk about on all fours everywhere he went, but he seemed unable to speak or even comprehend human language, answering all efforts to communicate with grunts, growls, howls, or whimpers. It was quickly deduced that this young boy must have been orphaned in the forest, where he had made an unlikely new family with the wolves.

At first the boy could not be approached, as he was every bit as vicious as the wolves that had been slain. He snapped and bit at anyone who would come near him, and he was only able to be gathered up when he ran out of energy to slump down by one of the dead wolves and bury his face in its fur as if in mourning. Even then, the boy put up a fight, but now they were able to subdue him and bring him to the Sikandra Mission Orphanage, in the city of Agra, where he was named Dina Sanichar, with “Sanichar” the local word for “Sunday” as that was the day on which he was brought in. They put him into a room but he would prove to be far from an ordinary boy. Not only did he nimbly walk about on all fours everywhere he went, but he seemed unable to speak or even comprehend human language, answering all efforts to communicate with grunts, growls, howls, or whimpers. It was quickly deduced that this young boy must have been orphaned in the forest, where he had made an unlikely new family with the wolves.

The orphanage did all they could for Sanichar, but they had to make a few adjustments to their normal way of doing things. For one, the boy at first absolutely refused to be dressed in clothes, tearing them from his body whenever they were put on him. He also would eat nothing but raw meat, refusing all other food offered to him, he would sharpen his teeth by gnawing on bones, and he showed absolutely no sign of normal human emotional expression, such as smiling or laughing. Try as they might, the missionaries were unable to teach Sanichar to speak, with him unable to grasp even the simplest of words, although he did show signs of intelligence beyond that of a mere wolf, and even began drinking out of a cup. One Father Erhardt, a missionary at the orphanage, would say of him, “while undoubtedly pagal (imbecile or idiotic), he still shows signs of reason and sometimes actual shrewdness.” Although he became less aggressive and more docile over time, Sanichar showed no willingness at all to form a bond with anyone at the missionary. Indeed, the only time he ever showed a bond with another human being was when another feral child like him was brought into the missionary, just as wild and animalistic as he was. These two wild children would form a quick friendship, cavorting about all fours together, curling beside one another at night, and Sanichar even taught the other how to use a cup. When his companion tragically passed away for unknown reasons, Sanichar purportedly spent long days howling with sadness, the first time he had shown any emotion other than rage and fear.

The missionaries continued to try to teach this boy how to be human, but progress was slow to nonexistent. They eventually taught him human behavior to some degree, such as eating from a plate with utensils, and they managed to get him to wear clothes and walk upright, although he was visibly uncomfortable doing so and had great difficulty dressing himself. In the nearly 20 years he would spend at the orphanage among humans, Sanichar never did graduate much from eating raw meat, although he would on occasion accept cooked meat, and he was never able to speak, read, or write, although he showed a rudimentary understanding of some simple words and phrases. Rather oddly, one human habit he took to quite fondly was smoking, and Sanichar was known to be a very heavy smoker, something which possibly helped him along to an early grave when he died of tuberculosis in 1895.

It is amazing how the vast gulf between the animal world he had left and the human world he then inhabited was never able to be fully crossed by him, the boy unable to fully adjust to the life that he should have had under normal circumstances. One quote on the site Amazing Cool Pictures says rather nicely of this innate awkwardness:

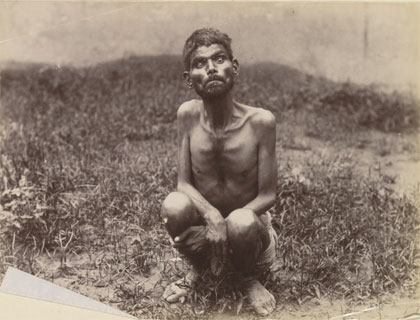

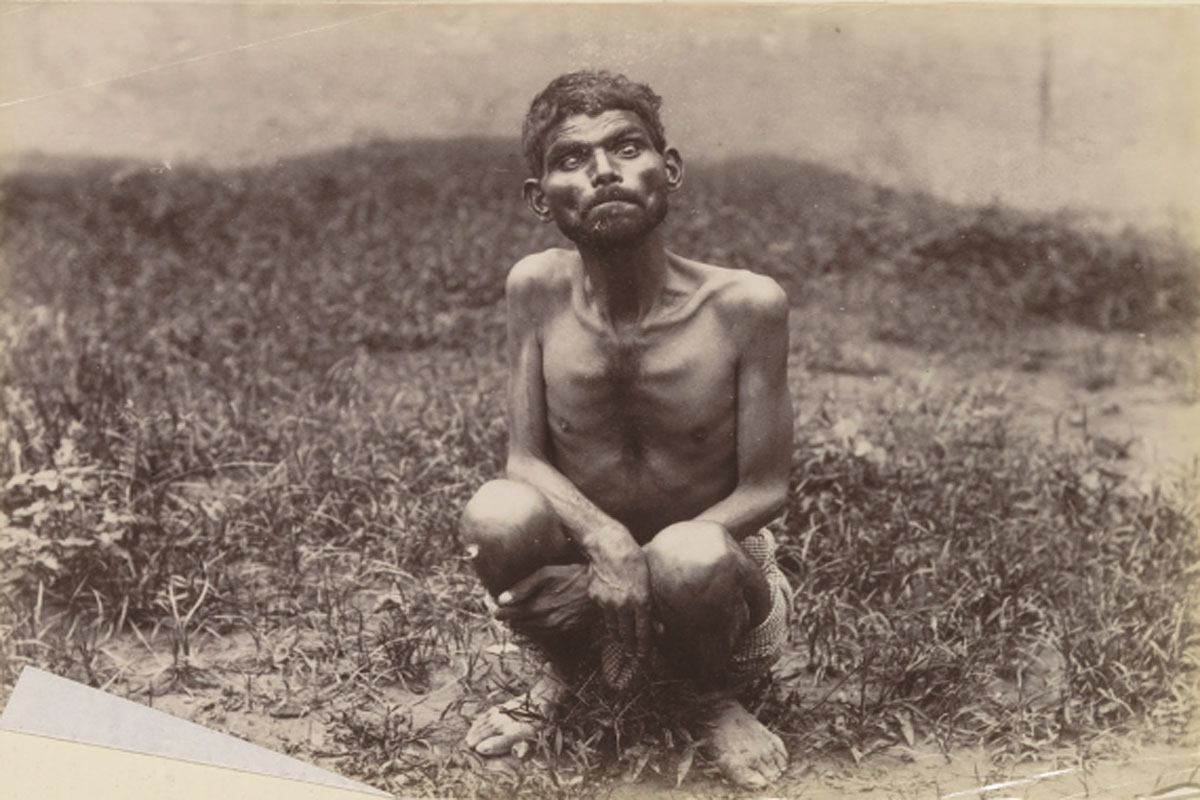

Sanichar is unnerving, perhaps because he lays bare the precariousness of the distinction between animal and human. A few years spent away from homes, cars, showers, and people, and we might more resemble the family dog than our human family. The few images of Sanichar that remain reveal a wild-eyed figure, his body contorted, as though he doesn’t understand how to be in it. The sight of him clothed is even more alarming — the trappings of civilization amplifying his wildness rather than concealing it. The feral child threatens to undo the hierarchy of biological beings where humans are at the top by forcing us to ask what we are.

It is widely thought that Sanichar at least partly inspired the character of Mowgli in Rudyard Kipling’s beloved tale The Jungle Book, who was also raised by wolves in the forests of India, and he remains one of the best-known examples of feral children, although there are many others. Such tales are intriguing in that they show us potential deep insight into human nature. What do these mysterious people like Sanichar tell us about the human condition? Are we made human by our surroundings, culture, and language? Are we civilized and tamed by society, yet harbor within us a more animalistic side that lurks beneath the surface, pulsing underneath the veneer of civilization? It seems that with these accounts of feral people we get a glimpse into that animal side, to see a raw, wild aspect to our nature that most of us will never experience, and perhaps this peek into this animal nature can give us insight on just what it means to be human. Whether Dina Sanichar found that lost humanity within himself or not will probably remain an eternal mystery.

MU*