11 WWII Questions Even History Buffs May Not Know The Answer To

Gordon Cameron

WWII is the ultimate historical rabbit hole. Thousands of books have been published about the biggest conflict in human history, and its vast scope means no one person can learn everything about it. From the famous battles, generals, and dictators, to the then-cutting-edge aircraft and equipment, to the social movements and civilian struggles that followed in its wake, there’s plenty for history buffs to immerse themselves in. Along the way, the attentive reader will learn facts that seem too weird to be true.

Even the most dedicated student of WWII, of course, will still have plenty of questions nagging them. Some are big questions about the great events and their causes; others are simple – even trivial – ones about terminology. Here are a few questions we didn’t know the answers to until recently.

________________________________________

• Photo: U.S. Air Force / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

• Photo: U.S. Air Force / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

1

What Happened To The Airmen From The Doolittle Raid?

Just four months after Pearl Harbor, American planes bombed Tokyo in a raid that was designed more to boost morale at home than to inflict serious damage on Imperial Japan. Sixteen B-25B bombers took off from the USS Hornet and attacked targets on the Japanese island of Honshu.

Because of the lack of Allied airbases in the Pacific at this early stage of the conflict, the attack was essentially a one-way ticket. With their planes low on fuel, the crews had to parachute out over China and crash-land their aircraft, then make their way home. (One plane landed in the Soviet Union; its crew was detained by the Soviets, who at the time had a non-aggression pact with Japan, but the Americans eventually escaped.)

Eighty American servicemen participated in the Doolittle Raid. Most of those were helped by Chinese civilians and soldiers. Doolittle himself, who commanded one of the aircraft, was helped by the American missionary John Birch, who would later become the namesake of a militant American anti-communist society.

Of those who didn’t make it back, three perished in action and eight were captured by the Japanese. Three of those were executed, one perished in captivity, and four were sent home after the war.

The last of them, Richard Cole, passed in 2019, at age 103.

• Enlightening answer?

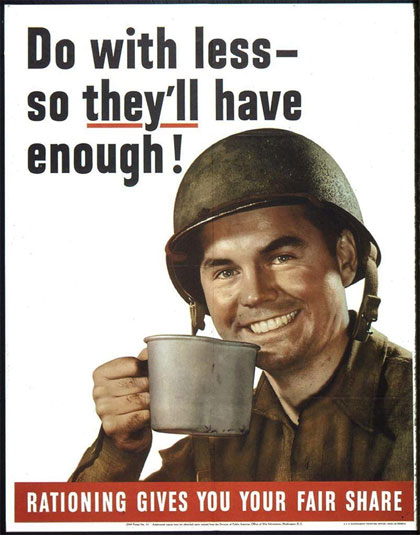

• • • Photo: Office of War Information / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

• • • Photo: Office of War Information / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

2

What Does ‘G.I.’ Stand For?

The initials “G.I.” evoke an image of the all-American soldier – the unpretentious grunt, weary yet determined, unglamorous yet competent, willing to do what it takes to get the job done. It became synonymous with “American infantryman,” and became a ubiquitous prefix. Soldiers returning from WWII got educations thanks to the “G.I. Bill,” one of most popular toys in the ’60s and ’80s was “G.I. Joe,” and Demi Moore put a gender twist on the term when she signed up to be an elite soldier in G.I. Jane.

So, what does “G.I.” actually stand for? Most of us have probably assumed it was something along the lines of “Government Infantry,” “General Infantry,” or perhaps a “Government Issue” label stamped on military rations and equipment.

All of those are wrong. In fact, “G.I.” stands for “Galvanized Iron.”

In the early 20th century, military trash cans and buckets were stamped with the initials, simply because galvanized iron was the material from which they were made. During WWI, the initials became a proxy for all things to do with infantry, and the usage stuck.

• Enlightening answer?

• • Photo: Ladislav Luppa / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

• • Photo: Ladislav Luppa / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

3

How Did The Axis Get Its Name?

The term “Axis,” as a reference to the powers aligned with Germany in WWII, was originally coined by Mussolini in a speech given on November 1, 1936, in which he outlined a new formal agreement between Germany and Italy. Speaking to a crowd in Milan, Il Duce said:

In addition to these four countries bordering Italy, a great country recently aroused vast sympathy from the masses of the Italian people: I speak of Germany. The meetings at Berlin had as a result an understanding between the two countries on definite problems, some of which are particularly troublesome these days.

But these understandings which have been consecrated and duly signed – this Berlin-Rome protocol – is not a barrier, but is rather an axis around which all European States animated by the will for collaboration and for peace may collaborate.

The so-called “Rome-Berlin Axis” was later extended to include Japan with the signing of the Tripartite Pact in September 1940.

• Enlightening answer?

• • Photo: Unknown / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

• • Photo: Unknown / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

4

Why Didn’t Spain Join The Axis?

German forces had aided the nationalist side in Spain’s Civil War of 1936-1939, and the man who emerged from that conflict as the supreme ruler of the country, General Francisco Franco, was in some ways aligned with fascism, although he didn’t explicitly endorse that ideology.

During WWII, Hitler made diplomatic overtures to Spain, hoping to secure an alliance with Franco’s government. But Franco refused to join the Axis, and Spain stayed largely neutral through the conflict. Why did Franco stay out – especially in 1940-1941, when Germany seemed to be running roughshod over continental Europe with no one able to stop them?

Franco met with the Third Reich leader in October 1940 to discuss the terms under which Spain might join the Axis. After hours of discussions, they were unable to come to an agreement. (Also, the German leader quipped that he would rather have his teeth pulled than meet with Franco again.) Evidently, Franco’s demands (including Gibraltar being handed to Spain upon Britain’s defeat, as well as cession of France’s North African colonies) were too greedy. What seems to have soured the negotiations was a reasonable hesitation on both sides. Hitler did not wish to alienate the pro-German Vichy government by conceding too many French territories, while Franco could not help but notice that, as 1940 wore on, Britain’s resilience was becoming increasingly apparent.

Later Franco apologists suggested that the Generalissimo, in his wisdom, perceived either the immorality of the Third Reich or its inability to achieve ultimate success, and so kept his distance. (Churchill wrote to US President Roosevelt, “I do not know whether there is more freedom in Stalin’s Russia than in Franco’s Spain. I have no intention to seek a quarrel with either.”)

In any case, Spain was not as aloof to Germany as has sometimes been claimed. The Francoist press remained pro-German even as the war was ending and the horrors of the Holocaust were coming to light, and Spain provided material aid such as the refueling and resupplying of German U-boats. After WWII, the press nimbly pivoted to praising Franco for keeping Spain at peace.

As the new priority in the West after 1945 was containing communism, American and British leaders chose not to look too closely at Franco’s prior dalliance with Germany. Franco would live (and remain in power) until 1975.

• Enlightening answer?

• • Photo: Casablanca / Warner Bros.

• • Photo: Casablanca / Warner Bros.

5

When Did It Start Being Called ‘World War II’?

Almost from the very beginning, it turns out.

Wars are named for all sorts of reasons, and often the names contain embedded political assumptions. (For example, it makes a big difference in the United States whether you’re talking about the “Civil War,” “The War Between the States,” or “The War of Northern Aggression.”) In the case of WWII, its predecessor – the global conflict from 1914-1918 – was originally known as the Great War (but sometimes also the World War). But when the new conflict began in 1939, it was obvious that it was closely related to the old one, and they became linked.

An October 1939 issue of Life magazine refers to it as “The European war” (p. 16) – which may indicate that, at that time, it was still seen (at least by some) as a rather localized affair involving England, Germany, France, Poland, and the Soviet Union (which had signed a peace treaty with Germany and was attacking Poland from the east). Japan’s incursion in China had already been going on for years, but it was not until America and England were drawn into the Pacific War in 1941 that the conflicts were seen as fully joined.

However, others were not hesitant to apply a global perspective from the very beginning. Indeed, a September 11, 1939 article in Time magazine – published just 10 days after the conflict started – began thus:

World War II began last week at 5:20 a.m. (Polish time) Friday, September 1, when a German bombing plane dropped a projectile on Puck, fishing village and air base in the armpit of the Hel Peninsula. At 5:45 a.m. the German training ship Schleswig-Holstein lying off Danzig fired what was believed to be the first shell: a direct hit on the Polish underground ammunition dump at Westerplatte. It was a grey day, with gentle rain.

In 1942, the film Casablanca opened with the words, “With the coming of the Second World War,” indicating that the usage was well cemented by the conflict’s fourth year.

• Enlightening answer?

• • Photo: U.S. Coast Guard / MIckStephenson / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

• • Photo: U.S. Coast Guard / MIckStephenson / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

6

What Does The ‘D’ In ‘D-Day’ Stand For?

D-Day looms large in the American mythology of WWII. It’s the day the Western allies really took the fight to Germany, opening up a second front with a massive amphibious invasion of France’s Normandy coast. Immortalized in films and series from The Longest Day to Saving Private Ryan and Band of Brothers, June 6, 1944, is a date writ large on the annals of history. But what does the “D” actually stand for?

You’d think it might be something cool, like “Decision” or “Determination” or “Doomsday.” But the truth is more mundane. According to the National WWII Museum, the “D” simply stands for “Day.” The term dates to a 1918 order during WWI, which specified that the First Army was to attack at “H-Hour on D-Day.” So essentially it’s a blank variable used to designate time without giving anything away to people who might intercept the message. Moreover, Normandy was not the only D-Day in WWII; every amphibious assault used the designation.

The editorial staff of Life magazine elaborated further, in a response to a letter in the June 5, 1944 issue (p. 8), from a reader who believed the “D” stood for “Debarkation”:

Often incorrectly translated as Dog, Debarkation, or Doomsday (for the Germans), the D of D-Day stands for nothing more sensational than the first letter of the word “day.” But this redundant device provides a handy time symbol. Invasion planners may speak of “D minus 7” or “D plus 4” for a particular day one week before invasion or four days after, thus giving an exact date but never revealing the true calendar day of invasion.

• Enlightening answer?

• • Photo: War Office official photographer, Captain Horton / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

• • Photo: War Office official photographer, Captain Horton / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

7

Did Britain Have An A-Bomb Program?

Given that British physicists were world leaders in their field and at the forefront of the newly emerging quantum physics, you’d think they would have been trying to develop their own atomic bomb during WWII. And you’d be right – though their project eventually became intermingled with the more famous American Manhattan Project.

In 1940, Winston Churchill established a committee, the MAUD committee, to investigate the possibility of making a nuclear weapon. Churchill said, “Although personally I am quite content with the existing explosives, I feel we must not stand in the path of improvement, and I therefore think that action should be taken…” The MAUD committee evolved into the Directorate of Tube Alloys, which was given a deliberately bland name for purposes of secrecy. Tube Alloys constructed a plant in Canada for the separation of Uranium-235.

By this time, the American atomic bomb program was also underway, and President Roosevelt contacted Churchill in 1941, advising collaboration. Churchill was initially reluctant, but the next year two Tube Alloys officials, Wallace Akers and Michael Perrin, made visits to the US facilities and were impressed with the rapid progress being made. Churchill was persuaded that collaboration made the most sense, and in 1943, the Quebec Agreement was signed, formalizing the arrangement.

Soon afterward, British scientists began to work directly on the Manhattan Project, although its director, General Leslie Groves, distrusted them and tried to restrict their access to secret information.

The passing of Roosevelt in April 1945 ended the chummy relationship between Britain and the US on atomic matters. After the war, Britain’s atomic program was more or less on its own, although the scientists who had worked on Manhattan were armed with a great deal of knowledge. The first British atomic bomb was successfully tested on October 3, 1952, at Monte Bello, Australia.

• Enlightening answer?

• • Photo: Johannes Hähle / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

• • Photo: Johannes Hähle / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

8

Why Didn’t Stalin Anticipate An Attack From Germany?

When Germany launched Operation Barbarossa – the massive attack on the Soviet Union – on June 22, 1941, its military achieved near-total surprise, which is shocking when you consider the sheer scale and logistical complexity of the assault. Stalin, who had signed a nonaggression pact with Germany in 1939 and shared in carving up Poland with the Third Reich, was stunned by this development, despite the heated anti-communist rhetoric that had emanated from German leaders for years. Why did the famously paranoid Stalin – who once purged the Red Army’s officer corps for fear of disloyalty – not see this coming?

In fact, there were warnings in the weeks before June 22 – from reports by Soviet spies, to German planes repeatedly violating Soviet airspace, to entreaties from both Winston Churchill and FDR that Germany was sure to turn its gaze on Russia. Even Polish women on the far bank of one frontier river shouted to Russian border guards, “Soviets, the war will start in one week!” But it was not until June 21, when a German soldier defected and warned the Soviets of the coming attack, that Stalin finally took the matter seriously. By then, it was too late to organize a proper defense, and Barbarossa got off to a terrifyingly effective start.

Interestingly, Stalin himself gave tantalizing hints that he perceived the danger. In a speech of May 5 to graduating Red Army cadets, Stalin addressed Germany’s seeming invincibility in a way that suggested he was considering the prospects of a coming conflict with the Third Reich:

In terms of equipment the German is nothing special. Now many armies, including our own, have similar equipment. And our aircraft are already better than those of the Germans. And on top of that the Germans have become dizzy with successes. Their military equipment is no longer getting better. The leaders of the army have become conceited, have a devil-may-care attitude.

The Russian historian Arsen Martirosyan has suggested that Stalin was slow to react to the various warning signs because he feared being influenced by German misinformation. This might also account for his dismissal of warnings by Churchill and Roosevelt; he didn’t trust either of them – sometimes with good reason. (The US and UK had teamed up for an abortive invasion of the Soviet Union at the end of WWI, and Churchill would consider doing so again at the end of WWII.)

Perhaps, in part, it comes down to this: If you trust no one, and doubt all sources of information, it’s difficult to prepare for the future.

• Enlightening answer?

• • Photo: Keating G (Lt), War Office official photographer / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

• • Photo: Keating G (Lt), War Office official photographer / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

9

Why Didn’t France And Britain Attack Germany In 1939-1940?

One of the oddest periods of WWII was the so-called “Sitzkrieg” or phony war, which lasted from September 1939 until the spring of 1940 on the Western Front. While both France and Britain had declared war on Germany following the invasion of Poland, the initial response was somewhat passive.

France had a standing army of some 900,000 men, considerably less than the more than 3 million mustered by Germany – but there were another 5 million French reservists who could be called up in time of need. Moreover, Germany was heavily engaged in Poland, meaning it might not have been able to bring its full strength to bear to repel a swift Franco-British invasion.

The French Third, Fourth, and Fifth Armies did make a probing attack into Western Germany in the first half of September 1939; this became known as the Saar Offensive. French troops advanced a few miles into Third Reich territory, but at the first sign of serious resistance, they withdrew. By October, most French forces were nestled behind the famous Maginot Line, where they (wrongly) believed they would be safe.

French and British commanders, presuming Germany would have to attack through Belgium as they had done in WWI, made plans for a counterattack, but were content to cede the initiative to Hitler. Meanwhile, the ostensible cause of the war declaration – Poland – was being greedily devoured by Germany and Russia, with no Allied intervention to speak of.

Part of the reason for this was psychological: the Western Front of WWI had been so horrific that French and British leaders were hesitant to embark on a sequel. The heavily fortified Franco-German border meant that a serious offensive would be up against difficult odds, and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain vetoed a proposed Allied attack through Belgium on the grounds that it would violate that country’s neutrality. (The Germans had no such scruple the following spring.)

Britain’s main action at that time was to institute a naval blockade that it hoped would sufficiently damage Germany’s economy. The weather also played a role: the winter of 1939-1940 was unusually cold, making military operations even more unattractive than they already were.

The Allies’ passivity would prove fateful when Germany finally turned its eye westward, beginning a devastating series of attacks against Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, and France.

• Enlightening answer?

• • Photo: Malindine E G (Capt), No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

• • Photo: Malindine E G (Capt), No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

10

Who Was The Last Leader Of The Third Reich?

For the vast majority of the Third Reich’s existence between 1933 and 1945, its supreme ruler was, of course, Adolf Hitler. (You could technically make the case that Paul von Hindenburg, president of Germany until his passing in 1934, was its first leader – depending on how you define ‘leader.’ He remained its head of state even as his Chancellor was consolidating power behind his back.) But although the Führer’s final days in the bunker in April 1945 are associated with the end of the war in Europe, the Third Reich actually survived him by several days.

By the time Hitler took his life on April 30, 1945, two of the presumptive heirs to his job – Reichsmarshall Herman Göring and head of the SS Heinrich Himmler – had become persona non grata with the Führer himself, thanks to behavior he considered disloyal. He named a naval officer, Admiral Karl Dönitz, to be his heir.

Dönitz ran the Third Reich – what was left of it – from the town of Flensburg, but with Berlin occupied by the Soviets and German lines of defense crumbling on all fronts, there was little he could do. After a few days of negotiation with General Eisenhower, Dönitz – who had vainly hoped to initiate a separate peace with the Western allies – issued an unconditional surrender on May 7, 1945, just a week after the demise of his old boss.

After the surrender, Dönitz was tried at Nuremberg and received a 10-year prison sentence. He lived until 1980.

• Enlightening answer?

• • Photo: Alfred T. Palmer / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

• • Photo: Alfred T. Palmer / Wikimedia Commons / Public domain

11

Was There An Actual Rosie The Riveter?

In WWII, as indeed in WWI, American women stepped in to fill in many of the traditionally male work roles that had been vacated by men signing up for the Armed Forces. By 1943, there were more than 300,000 women working in the aircraft industry alone.

The image of tough, determined female workers was used in Allied propaganda; the iconic image was created by J. Howard Miller in 1942 for a poster for Westinghouse Electric Corporation.

Norman Rockwell put his own stamp on the archetype with a 1943 cover for the Saturday Evening Post. The name apparently dates to a song recorded in 1942 by Kay Kyser and his orchestra.

Other recordings of the song were made, as well, including this one by Allen Miller and his Orchestra:

All the day long,

Whether rain or shine,

She’s a part of the assembly line.

She’s making history,

Working for victory,

Rosie – rrrrrrrrr – the Riveter.

A real aircraft worker named Rose Will Monroe was featured in government films promoting the war effort, but she may have been chosen because of her name, which coincidentally was the same as the one in the song.

The original Westinghouse poster may have been modeled on Geraldine Hoff Doyle, an employee of the American Broach & Machine Co. in Ann Arbor, MI. Or it may have been modeled on Naomi Parker Fraley, who worked at the machine shop in the Alameda Naval Air Station, and who was photographed in 1942 with a now-familiar bandana on her head.

So the answer to “was there an actual Rosie the Riveter?” is that there was – and there were probably more than one. But the Rosie the Riveter was a fictional construct created by different people in different media, all answering to the needs of the moment.

Enlightening answer?

ranker.com