Do Modern Tales of “Dogmen” Have Their Roots in Antiquity?

Micah Hanks November 21, 2021

For many decades—centuries, in fact—stories of large, humanlike monsters have been told in North America and other parts of the world. The most well-known among these, arguably, is the American Sasquatch, although similar creatures in various other regions are known by different names.

Although larger, hairier, and generally having a more apelike appearance than humans do, Sasquatch does not strain the boundaries of plausibility like many other purported mystery animals do.

Creatures that essentially resemble Sasquatch are known in the fossil record, and many have gone so far as to attribute its identity to Gigantopithecus blacki, the megafaunal ape known to have existed in parts of Asia as recently as the last ice age.

However, reports of other creatures have cropped up over the years as well, which suggests an animal not quite the same as Sasquatch, and not so easily placed within the primate family tree.

Since the 1980s, stories involving a creature resembling a large humanoid with a doglike head have proliferated in parts of the northeastern United States, particularly around Michigan and Wisconsin. Dubbed the “Michigan Dogman,” alleged reports of this creature date as far back as 1887, recounting an incident where a pair of Wexford County lumberjacks claimed to have observed such a creature. Similar accounts appeared during the ensuing decades, even resulting in a popular song about the creature that received airtime on Traverse City, Michigan’s WTCM-FM radio station.

Opinions remain divided about what, precisely, such stories entail. For those who may already be skeptical about the prospect of a large, undiscovered bipedal ape species that has managed to remain officially undiscovered in America, the notion that a similar animal with canine attributes goes beyond straining credulity. Meanwhile, even some proponents of the existence of Sasquatch (albeit those inclined to keep the discussion within what could at least be accepted in the paleoanthropological record) might argue that sightings of “dog men” are really just misidentifications, or perhaps even exaggerated stories involving Sasquatch encounters.

Opinions remain divided about what, precisely, such stories entail. For those who may already be skeptical about the prospect of a large, undiscovered bipedal ape species that has managed to remain officially undiscovered in America, the notion that a similar animal with canine attributes goes beyond straining credulity. Meanwhile, even some proponents of the existence of Sasquatch (albeit those inclined to keep the discussion within what could at least be accepted in the paleoanthropological record) might argue that sightings of “dog men” are really just misidentifications, or perhaps even exaggerated stories involving Sasquatch encounters.

Another interpretation of the dogman motif, however, involves the prevalence of such creatures in myths and traditions from around the world throughout time. Might there be some merit to the idea that beliefs in such creatures in America are but one instance in a much longer series of cultural traditions involving dog-headed or otherwise doglike monsters bearing human traits?

In the therianthropic imagery of ancient Egypt and its depiction of various gods, among these we find jackal-faced Anubis, a protector of tombs and god who oversaw the mummification process.

Elsewhere, Chinese legends of dog-people bearing similarity to Egypt’s Anubis also exist, of which Dutch ethnographer Johannes De Groot would be first to define as “Cynanthropes” in 1901, as discussed in his Religious System of China.

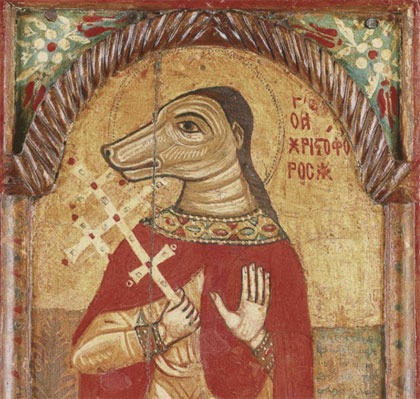

Some representations of Christian religious figures also bore doglike characteristics. German bishop Walther von Speyer, who wrote of Saint Christopher during the eleventh century in his The Life and Passion of Saint Christopher the Martyr, attributed the Saint’s fearsome appearance to his doglike face. Similarly, traditions in the Eastern Orthodox Church also depicted Christopher with the head of a canine.

Medieval depiction of Saint Christopher in his dog-headed form (public domain).

Medieval depiction of Saint Christopher in his dog-headed form (public domain).

“Christopher’s atypical physiognomy is derived from the accusatory words of the heathen king, Dagnus, when the king calls Christopher the ‘wyrresta wilddeor’ (worst wild beast),” wrote Medieval scholar Arthur J. Russell of the Saint’s canine appearance. “The king’s literal reading of Christopher overlooks the intrinsic virtue hidden beneath the dog-man’s horrific exterior. In this moment, Dagnus sees exactly what Christopher is—a monster and a threat to his way of being… Saint Christopher’s body is a body unlike any other because it challenges normative cultural values.

Later traditions that became prolific throughout parts of Europe in the Middle Ages involved human-canine hybrids in the form of werewolves. In countries like France and Germany, such traditions had become widespread enough by the early 1000’s that an early scientific epithet, melancholia canina, was given for the creatures (a later variation, daemonium lupum, dates back to the 14th century). For the most part, the belief in lycanthropes was associated with Satanism and witchcraft, as noted by Richard Verstegan in his 1628 Restitution of Decayed Intelligence.

According to Verstegan, the werewolf presence could be attributed to “certain sorcerers, who having anointed their bodies with an ointment which they make by the instinct of the devil, and putting on a certain enchanted girdle, does not only unto the view of others seem as wolves, but to their own thinking have both the shape and nature of wolves, so long as they wear the said girdle.

And they do dispose themselves as very wolves, in worrying and killing, and most of humane creatures.”

This notion that the werewolf’s appearance stems from his disassociation from God is a motif that had occurred far earlier than the prominent belief in were-beasts of the Middle Ages. In his Metamorphoses, the poet Ovid recounted numerous instances of transmogrification, among them that of the wicked King Lycaon, from whose name the word for the werewolf’s affliction, lycanthropy, is derived.

According to Ovid’s account, Lycaon had sought to test the power of the supreme god, Zeus, and chose to do this in a particularly vile way. One of a group of officials en route “from the Molossian state” was apparently accosted and murdered by Lycaon, who boiled the dead man’s flesh, laying “the mangled morsels in a dish” which he then served to Zeus (some legends state the remains belonged to a child, or even one of Lycaon’s own children). Zeus, realizing that the dinner before him is comprised of human remains, overturns the table in a rage, and burns Lycaon’s palace to the ground in “avenging flames.” The fiend, thus discovered, attempts to escape, but finds that his physical body has begun to change as he flees the angry god-king, who transforms him into a wolf.

Lycaon being transformed into a wolf, as envisioned by Hendrik Goltzius (public domain).

Lycaon being transformed into a wolf, as envisioned by Hendrik Goltzius (public domain).

The story of Lycaon also served as the inspiration for annual festivals held by night in early May of each year, appropriately called the Lykaia, which were performed on the slopes of Mount Lykaion near Arcadia in Ancient Greece. According to classical scholar Arthur Bertrand Cook, the fact that the wolf (the Greek word for this being lýkos) was featured so prominently in the local myths of the area indicated that perhaps Zeus himself, also given the nickname “Lýkaios” in the relevant legends, “was in some sense a ‘Wolf-god’.”

During the second century, the traveler and geographer Pausanias recorded the story of an Olympic boxer from the Lykaia festival’s home in Arcadia, who was said to have transformed into a wolf during the annual ritual. The story of this boxer, whose name was Damarchus, Pausanias tells us that he “cannot believe… what romancers say about him, how he changed his shape into that of a wolf at the sacrifice of Lycaean (Wolf) Zeus, and how nine years after he became a man again.”

These early classical references are paralleled somewhat by the writings of the Greek historian Herodotus, who would also discuss European wolfmen in his Histories, describing a race of people known as the Neuri that resided to the north around parts of modern-day Belarus and Poland. These men were said to transform into wolves once every year, based on Scythian folk tales of the period.

Plenty of similar examples exist in other traditions from around the world as well, which does beg the question: do the modern sightings of a “dogman” associated with various midwestern states have their basis in something else entirely? If so, does that involve the existing traditions regarding creatures like Sasquatch, or do the modern cases from Michigan and other states actually have their roots in antiquity, bearing something in common with the various traditions of Saints and other figures who have been depicted as “dogmen” since much earlier times?

MU*