14 Weird Facts About The History Of Halloween Around The World

Jon Skindzier

The history of Halloween seems to invite misinformation – the entire holiday is fraught with it. Many urban legends suggest that children are in danger of receiving apples full of razor blades; a vile Satanist may lurk behind every mailbox; and all unfamiliar-looking candy is likely ecstasy, apparently handed out by some poor soul overburdened with too much MDMA lying around. In reality, of course, reported cases of tainted Halloween candy are next to nothing, and the chances you will become a victim of human sacrifice is roughly the same as being slain by a meteorite.

Halloween in history is just as murky; it has a few separate origin points that all tie together, and its celebration often cobbles together local customs from preexisting holidays. It undoubtedly owes something to the Celtic festival of Samhain, but it’s hard to say with certainty what traditions come from where, especially since many of the only written records derived from the Romans.

We can at least be sure that the early Halloween was not, as was suggested, a holiday when druids showed up to your house to kill your sheep unless you gave them money.

________________________________________

• We Owe The Irish And Scottish For Having A Recognizable Halloween In America

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

The Protestant colonies were not exactly receptive to the idea of Halloween. The Puritans were so strict that the people of Boston banned Christmas celebrations in the mid-17th century, considering it blasphemous to observe a day with the vaguest of pagan origins; obviously, a holiday based on spooky ghosts and divination rituals did not stand a chance. Parts of colonial America did have festivities, but they weren’t widespread, and most Americans at the time viewed Halloween as strange and foreign.

Later immigrants, especially Irish immigrants fleeing the potato famine in the mid-19th century, brought over customs that were absent in the US, helping to universalize a holiday that might have otherwise flown under the radar.

• • At One Time, Halloween Simply Involved Blowing Stuff Up

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

There are little to no references to the practice of trick-or-treating as we currently recognize it in the United States before the 1930s. Instead, early accounts in America mostly focus on the mischief, which ranged from harmless – such as ringing doorbells and running away – to dangerous, including breaking windows and setting fires. Knocking over water tubs was also popular.

Especially notable was Halloween of 1913 in Sheffield, AL, when neighborhood kids planned to fill the town cannon with gunpowder and detonate it in the middle of the night.

The kids were, unsurprisingly, not experts at measuring out gunpowder, and they instead set off an explosion so loud that townspeople had assumed there was an earthquake. The cannon itself was thrown hundreds of feet from its foundation, and all of the windows on the hotel facing it had shattered.

• • Jack-O’-Lanterns Were Originally Carved From Turnips

Photo: Rannpháirtí anaithnid / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Photo: Rannpháirtí anaithnid / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA 3.0

The first jack-o’-lanterns were fashioned from turnips and potatoes to ward off “Stingy Jack,” a legendary figure who was so insufferable that he was barred from entering Heaven and had previously tricked the Devil into guaranteeing that he wouldn’t go to Hell either. In some versions, Jack convinces the Devil to turn into a coin so they can buy alcohol and get drunk together. In any case, Jack wound up with nowhere to go, doomed to wander Earth, lighting his way with a burning ember inside a hollowed-out turnip – hence “Jack of the Lantern.”

Jack-o’-lanterns in other regions were made from apples, squashes, and even cucumbers. Similarly, Germany has Rübengeister – “root-vegetable ghosts” – carved from potatoes or beets.

• • Halloween Was Ideal For Women To Spell Their Future Husband’s Name With Apples

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

Halloween and its predecessor holidays have always been considered ideal for fortune-telling and divination; Samhain was, after all, a time when the veil between the worlds of the living and dead was at its thinnest. Naturally, the best application of this access to the realm of the dead was to ask the ghosts which boy you would marry. A woman would pare an apple, throw the skin over her shoulder, and peel’s resulting shape would indicate her future husband’s initials. Or, she could approach the first man she saw on All Souls’ Day, and that guy’s name would resemble her future husband’s.

Alternatively, she could walk around a church three times and make a wish. The Irish also made barmbrack, bread that had a bunch of junk baked into it – usually fruit – and indicated your future based on what your slice contained: a coin indicated wealth; a cloth indicated bad luck; and a ring, of course, indicated upcoming marriage, evidently the single issue that anyone cared about back in the day.

• • World War II Canceled Halloween

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

The holiday ran into a bit of a rough patch in the late 1930s and early 1940s. On October 30, 1938, Orson Welles famously read a radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds on the air and thereby convinced millions of people that they were under attack by Martians. A few years later, when America was fully involved in World War II, some Halloween celebrations were canceled entirely.

Chicago’s City Council voted to cancel Halloween for the duration of the war in 1942, not only because of all of the mischief associated with the holiday, but also due to sugar rationing. It also struck people as a bit morbid to make light of death when a large portion of the population was off fighting Nazis.

• • Anoka, Minnesota, Was Home To The First Citywide Halloween Celebration

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

A city in the southern part of Minnesota, Anoka is one of the first American towns to distract roving youths from Halloween mischief with an organized celebration. A citywide parade was first organized in 1920, at which time Halloween wasn’t as organized as it is today – there wasn’t any recognizable trick-or-treating in America at that point, for example. The event grew to include fireworks, races, pillow fights, and other festivities.

It hosted 20,000 spectators, an amount higher than the population of the town in the 1930s. These days, the parade attracts double that number and lasts two hours.

• • Halloween Integrates Existing Customs, From Hiding Knives To Eating Skeleton Candy

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

Germans take care throughout All Souls’ Week to hide their knives from ghosts. In Eastern Europe – which includes Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic – All Souls’ Day involves leaving doors open and placing empty chairs by the hearth for the ghosts of one’s ancestors. Mexico celebrates Dia de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, a fusion of a pre-Columbian Aztec festival honoring the goddess Mictecacihuatl and Catholic beliefs brought by the conquistadors.

Dia de los Muertos presupposes that the dead would be honored more by revelry than grief, and the holiday focuses on feasting, drinking, and celebration. It is also one of the only situations in which you will see a procession of cheerful, upper-class lady skeletons.

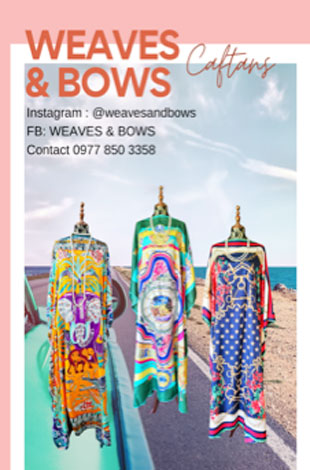

• • Shakespeare Mocks Trick-Or-Treaters In ‘The Two Gentlemen Of Verona’

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

Well, more accurately, he mocks the early predecessors to trick-or-treaters. In The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Valentine’s servant, Speed, teases him for his lovesickness, saying that Valentine has started to sigh like a schoolboy, to “watch, like one that fears robbing; to speak puling [whining], like a beggar at Hallowmas.” The comparison to a whiny Hallowmas beggar is a reference to the medieval custom of “souling,” which involved traveling door to door on All Hallows’ Eve and either singing for the homeowner or praying for their family. The compensation for the beggar’s prayers was supposed to be a “soul cake,” a cake topped with a cross design and sweetened with molasses, nutmeg, raisins, or cinnamon.

The tradition still exists in Portugal as Pao Por Deus, “Bread in the Name of God,” when children go from house to house reciting rhymes in return for bread or sweets.

• • We Owe Some Halloween Symbology To Mosquitoes, Perhaps

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

Most Halloween symbols have an apparent origin. Black cats, for example, were thought to be witches’ familiars or shape-shifted witches themselves, going back to the Middle Ages. Spiders are so innately threatening that even babies who don’t properly understand what they are can recognize their shapes. Bats, on the other hand – and their association with Halloween – are a bit of a mystery. One theory is that Samhain, a festival that involved lots of bonfires, might have attracted a lot of flying insects, which in turn attracted hungry bats.

It’s also possible that there’s no logical progression to the image at all, and that October happens to be a month when bats are everywhere – in the Northeastern United States at least.

• • Witches Are Associated With Halloween Because Of A Massive Execution

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

The friction between Christianity and pagan traditions has influenced Halloween since the beginning, but one event helped link Halloween and witches specifically. In 1589, King James VI sailed across the North Atlantic to retrieve Anne of Denmark. On the return trip to Scotland, the king’s ship faced storms so turbulent that it was forced to turn back; naturally, everyone concluded that witches caused the disturbances.

More specifically, they concluded that the Devil himself had appeared in North Berwick on Halloween in 1590, and instructed a bunch of witches to recite spells and fling a cat into the water until a storm killed the king. This ingenious plan is only attested by the “confessions” of the dozens of people who were poorly treated until they admitted to colluding with the Devil in the North Berwick church. In the end, over a hundred people were arrested – and hundreds or thousands would be similarly detained and executed for witchcraft in subsequent years.

• Halloween Was Once Overseen By A ‘Lord Of Misrule’

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

Also known as the “Abbot of Unreason” in Scotland, the Lord of Misrule was appointed on All Hallows’ Eve for the upcoming Christmas season. Again reflecting a time of year when everything was upside down and backward, he was essentially an official jester tasked with overseeing celebrations and being ridiculous. This whole commoner-as-king concept goes back to the Roman Saturnalia, a holiday that flipped the script on all of the usual social mores. For example, masters dined with their slaves, gambling was encouraged for a day, and everybody got as drunk as possible.

Saturnalia shares similarities with Babylonian “Mock King” celebrations, though these were not quite as fun – the fake king got to live like royalty for five days and was then scourged and executed.

• • The Oldest Halloween Traditions Involved Crossdressing

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

Dressing up as something else has remained central to Halloween since its inception. The Celts blackened their faces and wore animal skins as costumes; in some cases, they would carry a horse’s skull or a wooden horse head with working mechanical jaws on a pole. Keeping with the general Samhain theme of inversion and disorder, the usual social order was turned upside down – men could disrespect their elders, and gender norms could be ignored. The most obvious reflection of this was dressing up as the opposite sex.

In Wales specifically, young men dressed in women’s clothes and were referred to as gwrachod or “witches.”

• • The Roman Halloween Involved Feeding Beans To Ghosts

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

Aside from Samhain, the other day from which Halloween took its cues was Lemuria, or the Lemuralia, a day in which the ancient Romans attempted to placate their ancestors’ ghosts, or “lemures,” with a ceremony that involved taking off their shoes, cleaning their hands, and throwing beans all over the house. As the head of the family wandered around getting beans everywhere, the rest of the family followed the head around banging pots and pans together, hopefully expelling the ancestor ghosts.

The whole month was thought to be unlucky, which is probably one of the reasons May was – and is – considered an inauspicious month for weddings. Eventually, Christianity adopted Lemuria as a day sacred to all the martyrs, then finally moved it to November 1 – All Saints’ Day.

• • Halloween Originated With A Big, Drunken Tax Day

Photo: Getty Images: Matt Cardy / Stringer / Getty Images News

Photo: Getty Images: Matt Cardy / Stringer / Getty Images News

The most direct predecessor of Halloween is the Celtic Samhain, which had a lot going on, relatively speaking. It was a harvest celebration, a time to slaughter cattle for the coming winter and get drunk – which was apparently a rare occurrence back then. Since it was somewhat like a New Year celebration for the Celts, it also had an administrative purpose – people paid their taxes, settled their debts, and brandished the tongues of their slain enemies. Some warriors would even try to pawn off ox tongues as battle trophies instead.

A few of the Samhain traditions survive in a recognizable form – like apple-bobbing – while others did not quite make the cut, such as executing criminals.

ranker.com