Weather Control and the Weird Story of an American Rainmaker

Brent Swancer December 29, 2021

Mankind has long sought to dominate our world and control the natural forces around us, beating into submission all natural laws that stand in our way. Nothing has apparently been safe from our journey towards total mastery of this world, from changing environments to the tinkering of the very building blocks of life, and one feature of this landscape is that of trying to hold mastery over the weather itself. This desire has long been strong with us, graduating from the mystical rain dances of centuries past to more modern day technology, all seeking to gain control of the very weather itself. Here we get into the weird world of trying to manipulate and control the weather, and there have been many tales of those who would try, including that of a man who was renowned as a rainmaker and who would gather to himself quite the tale of weather control, subversion of the natural laws of the world, and tragedy.

Earnest attempts at weather control are nothing new. In as early as the late 19th century and the early 20th century there were already plenty of attempts to artificially make it rain, to varying degrees of success. It was called “pluviculture,” or basically the “science” of making it rain. To call it a science is a slippery term, as it was mostly based on shaky or even downright bogus claims, making it all well-suited to the domain of various charlatans, conmen, and traveling salesmen. In later years the idea of “cloud seeding,” or loading clouds up with various chemicals in order to change their chemical composition and induce precipitation has become more scientifically accepted, although controversial to this day, but back in the 19th and 20th centuries it was very much a fringe area existing side by side with magic and rain dances, and this was the world in which a man named James Hatfield would emerge to make a name for himself as a powerful rainmaker, who was either a genius, a charlatan, or both.

Born in 1875 in Fort Scott, Kansas, Charles Mallory Hatfield’s early life and career didn’t seem to suggest his future as a self-proclaimed master of weather control. He was born into a devout Quaker family of humble farmers, going on to become a salesman for the New Home Sewing Machine Company, and there was nothing at all to suggest that he had anything to do with creating rain, but in his free time he pursued pluviculture, fascinated with the possibilities it could bring. In 1902, after much experimenting at his parents’ ranch, he claimed to have discovered a secret formula of 23 chemicals that he proclaimed could be dispersed into the air from tall wooden towers perched on stilts to induce rain in even the driest and most parched conditions.

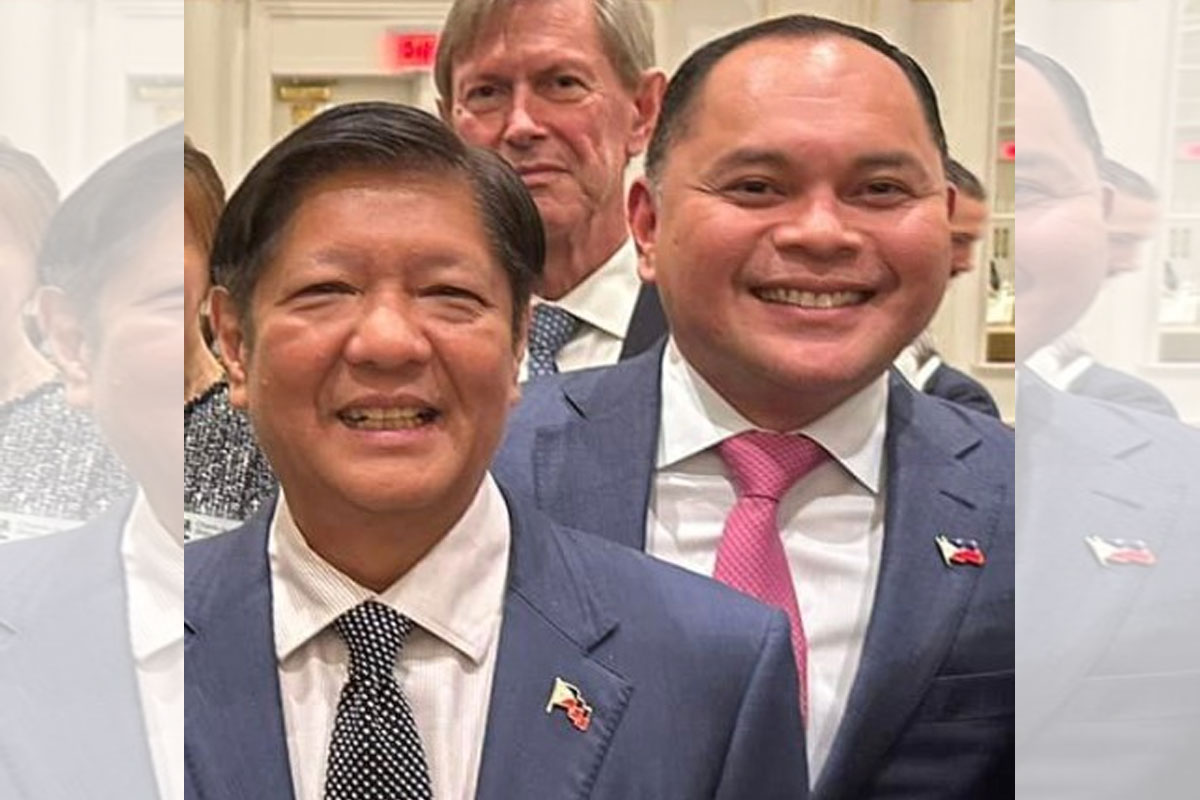

Charles Mallory Hatfield

Charles Mallory Hatfield

Hatfield began peddling his secret recipe for making it rain to farmers dealing with parched conditions in California, calling himself a “moisture accelerator” and promising that with his amazing method he could wring rain from the clouds within 3 to 5 hours of unleashing his foul-smelling chemical concoction. For this service he would charge $50, only to be paid if the promised rain came, and to the surprise of many, he seemed to be successful more often than not. Word got around about Hatfield’s purported abilities, and in December of 1904, he convinced Los Angeles business leaders that he could get 18 inches of rain to fall over five months with his technology in return for $1,000, and when this seems to have actually worked his reputation skyrocketed into the stratosphere, with him appearing in numerous news publications and magazines nationwide and becoming much in demand. He would begin securing contracts to make it rain all over the country along with the help of his two brothers, his rates ballooning up into thousands of dollars for just a few inches of rainfall, and he would say of his talents:

The twentieth test of my system has proved a perfect success I think that it has been clearly demonstrated that I can bring rain. I do not make rain. That would be an absurd claim. I simply attract clouds, and they do the rest.

Before long, Hatfield had a legion of supporters, and even his failures could not sway him. In 1906, he was hired by the Yukon Territory, in Canada, on a $10,000 rainmaking contract, but failed, receiving $1,100 for nothing and slinking back off to the States. However, even with this setback his reputation was set. His business boomed, raking in tons of money and accolades, and this was what brought him to the attention of the city of San Diego, California in 1915. At the time, San Diego was in the midst of a terrible drought, with the water starved city having some of the driest times it had ever experienced. Farming was suffering, the reservoir was drying up, the Panama-California Exposition had opened in San Diego, and they were desperate to have rain by any means necessary, not only out of necessity, but to show their city to the world at the exposition in the best light.

The San Diego city council brought Hatfield in, who promised that by making a tower next to the drying Morena Dam reservoir, which was only one-third full at the time, he could fill it back up in no time for $1,000 per inch, eventually settling for a flat $10,000 fee to be payable only if he succeeded. He claimed that he would get the reservoir full, promising it would happen within the year and got to work. At the time, there were plenty of skeptics and naysayers surrounding the whole ambitious plan, but considering that there would be no money paid unless there were results, it was largely allowed to go forward unimpeded, the news watching Hatfield’s every move and the public looking on with a mixture of excitement, wonder, and incredulity. Hatfield would soon prove the haters wrong, but also turn out to by all appearances be maybe a little too good at what he did.

Within a month of setting up shop and beginning his mysterious process, San Diego County began to experience rain, and not just a little bit, but a full-on deluge. Indeed, it was one of the wettest periods San Diego had ever experienced in its recorded history, with the heavy rains to the tune of 17 inches of rain over five days causing massive floods throughout the region that would end with overflowed dams, landslides, cut phone cables, washed out bridges, destroyed homes and farms, and resulted in $3.5 million in property damage and at least 22 people dead, with some estimates putting the death toll as high as 50. In the end, 30 inches of rain would fall within a month, breaking records and indeed considered to this day to be one of the worst weather events to ever strike the city. Of course, considering the timing of all of this all eyes were on Hatfield, but he refused to take the blame for the damages and insisting that his end of the contract should be honored, as the reservoir was now most certainly full. The city council refused, it went to court, and Hatfield tried to settle for $4000 and then sued the council. The case would stretch on for decades, not helped by the fact that there had never been a formal contract, before in 1938 finally being considered an act of God, absolving Hatfield from any wrongdoing but also making sure he didn’t get his money.

Within a month of setting up shop and beginning his mysterious process, San Diego County began to experience rain, and not just a little bit, but a full-on deluge. Indeed, it was one of the wettest periods San Diego had ever experienced in its recorded history, with the heavy rains to the tune of 17 inches of rain over five days causing massive floods throughout the region that would end with overflowed dams, landslides, cut phone cables, washed out bridges, destroyed homes and farms, and resulted in $3.5 million in property damage and at least 22 people dead, with some estimates putting the death toll as high as 50. In the end, 30 inches of rain would fall within a month, breaking records and indeed considered to this day to be one of the worst weather events to ever strike the city. Of course, considering the timing of all of this all eyes were on Hatfield, but he refused to take the blame for the damages and insisting that his end of the contract should be honored, as the reservoir was now most certainly full. The city council refused, it went to court, and Hatfield tried to settle for $4000 and then sued the council. The case would stretch on for decades, not helped by the fact that there had never been a formal contract, before in 1938 finally being considered an act of God, absolving Hatfield from any wrongdoing but also making sure he didn’t get his money.

It did little to damage Hatfield’s reputation, and in fact only bolstered his place as an expert rainmaker. Throughout the court proceedings he would continue to get several more lucrative contracts, in places as far away as Honduras, including one for $25,000 to bring five inches of rain to Medicine Hat, Alberta, Canada, but the Great Depression would see his business plummet, forcing him back into the sewing machine business. Hatfield would experience a series of blows, including seeing his rainmaking business buckle and his wife leave him, before dying in January of 1958 to take his secret rainmaking formula to the grave with him. He would die with his reputation in tact though, considered probably the most well-known and successful rainmakers to have ever lived, but of course there has been much skepticism aimed at it all.

While many sing Hatfield’s praises as a pioneer of cloud seeding and weather control technology, there is also the fact that many of these rainmakers of the time were very clever conmen. They were well-versed in meteorology and weather patterns, using this knowledge to time their procedures and utilizing this, coincidence, and sheer luck to sell the illusion that they were the cause of the rain. In the case of Hatfield and the San Diego floods, he was probably very aware that the region experienced flooding roughly every 11 years and was overdue for it at the time, and so used that knowledge to time his demonstration during a period with a high probability of rains, with luck, or ultimately the opposite in this case, doing the rest. His keen knowledge of meteorology and close examination of weather records would have absolutely helped him sell the illusion here, but whether that was really the case or not remains unknown. Yet, what if there was a small chance that he was actually onto something and his formula worked? To this day no one really knows, and it remains a curious historical oddity and testament to our desire to tame the natural forces of our world.

MU*