The Time Mark Twain Wrote a New Novel From Beyond the Grave

Brent Swancer January 8, 2022

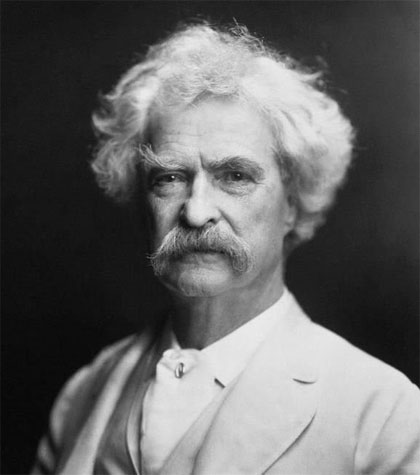

The sad thing about death and geniuses is that their mark on the world ends with the tossing of their mortal coils, but what if that weren’t the case? The writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer Samuel Langhorne Clemens, more popularly known by his penname Mark Twain, is without a doubt one of the greatest American authors of all time. Often called “the father of American literature,” he is most famous for his works The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and its sequel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), with the second one often listed high among the greatest novels ever written. His books have been beloved around the world, translated into many languages, and even people who don’t know anything about literature at all know the name Mark Twain. When Twain died in 1910, the public and the literary world mourned the loss of this great mind, yet it doesn’t seem as if death stopped him, as one of his stranger and more obscure works is a novel that was claimed to have been written from beyond the grave.

The story here begins with a self-proclaimed psychic medium by the name of Emily Grant Hutchings, and while this may have some people rolling their eyes already she was not immediately identifiable as any sort of quack or charlatan. Hutchings was born Emily Schmidt, in Hannibal, Missouri to a prominent family, her father being Carl H. Schmidt, an official of the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railway Company, and her mother, Margaret, the daughter of a German noble family and holding the reputation of being one of the first female physicians in the Mississippi Valley. She went through school with flying colors, going on to teach Latin, Greek and German at a high school before becoming an esteemed writer for such publications as the St. Louis Republic newspaper and Cosmopolitan, Country Life, Current Magazine, The Open Court, and Atlantic Monthly magazines, also writing extensively to promote the World’s Fair in St. Louis and several novels. She even met Mark Twain himself briefly in 1902 while attending a luncheon with her husband, Charles Edwin Hutchings, and received some minor correspondence with him in which he advised her on her writing. So far there is nothing particularly strange at all about it, with Hutchings seeming to be an intelligent, successful, and sane woman, but her life would get very weird.

Mark Twain

Mark Twain

At the time, the Spiritualism movement was still going strong in America, with séances and communicating with the spirits of the dead very popular. Hutchings got caught up in it all when she and a medium named Pearl Lenore Pollard began receiving communication via a Ouija board from a spirit calling herself “Patience Worth,” who also allegedly happened to be a writer. Hutchings would help Patience posthumously write her poetry, short stories, and several novels. In 1915, Hutchings was carrying out one of these Ouija board sessions with Patience Worth when it was rudely interrupted by a spirit claiming to be Mark Twain, and who called Hutchings “the Hannibal girl.” Hutchings became completely enthralled with the idea that Twain had communicated with her from beyond the grave, convinced that what she had experienced was real. Wishing to keep up this spiritual correspondence, she took to using the Ouija board to try and contact him again, and it would seem she would be successful.

With the help of a spirit medium named Lola V. Hays, Hutchings would claim that she had not only struck up a conversation with the very dead Mark Twain, but that he had requested that she transcribe a new novel for him, which she accepted. Over the next two years, Hutchings and Hays would claim that they had used the Ouija board to meticulously take down Twain’s every word, eventually completing two short stories, and a novel titled Jap Herron, which they would go ahead and publish in 1917 through the renowned book dealer Mitchell Kennerley. The book quickly shot to fame when The New York Times ran a review of it, and considering the popularity of spiritualism and Ouija boards at the time, a lot of people really believed that this was a new book from the dead Mark Twain, and that Hutchings and Hays were telling the truth, despite the fact that the review was less than flattering.

Indeed, while many were eating this stuff up, many reviewers and literary critics were not so convinced. Besides the fact that they were dealing with a novel supposedly written by a ghost through a Ouija board, there was also the fact that the book itself just didn’t feel like a Twain novel. While there were some superficial stylistic resemblances, Jap Herron largely lacked the intelligence, wit, and trademark writing style the author had, the story’s structure didn’t feel right, and the characters were unlike anything one would expect to populate any world thought up by Twain. In short, it was seen as a not particularly well-written piece by someone doing a bad imitation of Twain. Many reviews brutally drubbed the book, with the one in The New York Times reading in part:

Indeed, while many were eating this stuff up, many reviewers and literary critics were not so convinced. Besides the fact that they were dealing with a novel supposedly written by a ghost through a Ouija board, there was also the fact that the book itself just didn’t feel like a Twain novel. While there were some superficial stylistic resemblances, Jap Herron largely lacked the intelligence, wit, and trademark writing style the author had, the story’s structure didn’t feel right, and the characters were unlike anything one would expect to populate any world thought up by Twain. In short, it was seen as a not particularly well-written piece by someone doing a bad imitation of Twain. Many reviews brutally drubbed the book, with the one in The New York Times reading in part:

There is evident a rather striking knowledge of the conditions of life and the peculiarities of character in a Missouri town, the dialect is true, and the picture has, in general, many features that will seem familiar to those who know their ‘Tom Sawyer’ and ‘Huckleberry Finn’. A country paper fills an important place in the tale, and there is constant proof of familiarity with the life and work of the editor of such a sheet. The humor impresses as a feeble attempt at imitation and, while there is now and then a strong sure touch of pathos or a swift and true revelation of human nature, the ‘sob stuff’ that oozes through many of the scenes, and the overdrawn emotions are too much for credulity. If this is the best that ‘Mark Twain’ can do by reaching across the barrier, the army of admirers that his works have won for him will all hope that he will hereafter respect that boundary.

In the meantime, Hutchings and Hays continued to insist that they were telling the truth, and that not only was Jap Herron really written by Twain from the afterlife, but that he had even started to write another through them, titled Brent Roberts. Hutchings would further claim that she had never even read Mark Twain before, which seems unlikely considering that she was so well educated and a writer herself. Psychologist and psychical researcher James Hyslop, of the Society for Psychical Research, would investigate the claims and come away on the fence about whether the two women were telling the truth or not. As all of this was going on, Twain’s daughter Clara Clemens stepped in to make matters more complicated by filing a lawsuit in the Supreme Court against Hutchings and her publisher Mitchell Kennerley in order to stop them from making any money off of her father’s name, demanding that publication of the book immediately be stopped and all copies destroyed.

Clemens and her lawyers tried the tact of demanding that the two mediums either admit that the book was a fraud or donate any proceeds for it to the Mark Twain estate and the publisher Harper & Brothers, who at the time had sole rights to the publication of Mark Twain stories. Clemens basically came at them with a claim of copyright infringement, but since it is difficult to make that stick with a dead author channeling a work through a spirit medium, it was not a case that stood a good chance of succeeding. Even so, it was still a situation that had Hutchings between a rock and a hard place, since she essentially would have to either prove that the book was written by the ghost of Twain or publicly admit to being a fraud. With potential legal problems circling like vultures, Hutchings and Hays nevertheless ended up agreeing to halt publication of the book and remove all copies from stores, and the lawsuit never made it to trial. To this day an actual physical paper copy of the book is extremely rare, although it can be read digitally online for free.

Clemens and her lawyers tried the tact of demanding that the two mediums either admit that the book was a fraud or donate any proceeds for it to the Mark Twain estate and the publisher Harper & Brothers, who at the time had sole rights to the publication of Mark Twain stories. Clemens basically came at them with a claim of copyright infringement, but since it is difficult to make that stick with a dead author channeling a work through a spirit medium, it was not a case that stood a good chance of succeeding. Even so, it was still a situation that had Hutchings between a rock and a hard place, since she essentially would have to either prove that the book was written by the ghost of Twain or publicly admit to being a fraud. With potential legal problems circling like vultures, Hutchings and Hays nevertheless ended up agreeing to halt publication of the book and remove all copies from stores, and the lawsuit never made it to trial. To this day an actual physical paper copy of the book is extremely rare, although it can be read digitally online for free.

Even after all of this, Hutchings would insist that she was telling the truth right up until her death in 1960, never backing down from her claims. What are we to make of all of this? Of course, considering the quality of writing and the atmosphere of the era, it very much seems that this was a grand hoax perpetrated by some questionable mediums, but was there perhaps something more to it? It is all a wild ride no matter what the case may be, and at the very least food for though to make one think about what could actually be possible if some of our greatest minds were allowed to somehow continue working from the grave.

MU*