Nessie: Forget the First Famous Sighting, What About the Second One?

Nick Redfern September 23, 2021

Much has been written about the very first encounter with the Loch Ness Monster(s). But, what about the second case? It’s an affair that is very intriguing. It’s also a case that has largely been forgotten. Before the Loch Ness Monster there was the River Ness Monster, something that leads into the famous loch. It is highly ironic – considering the many attempts that have been made by monster-hunters to suggest the Nessies are plesiosaurs, salamanders or giant eels – that even the very first, reported encounter with one of the creatures of Loch Ness was steeped in occult mystery. It’s a certain St. Adomnán who we have to thank for bringing this intriguing case to our attention. The story can be found in Book II, Chapter XXVII of St. Adomnán’s Vita Columbae. To say that it’s quite a tale is, at the very least, an understatement. Born in the town of Raphoe, Ireland in 624 AD, St. Adomnán spent much of his life on the Scottish island of Iona where he served as an abbot, spreading the word of the Christian God and moving in very influential and power-filled circles. He could count amongst his friends King Aldfrith of Northumbria and Fínsnechta Fledach mac Dúnchada, the High King of Ireland. And he, St. Adomnán, made a notable contribution to the world of a certain, famous lake-monster.

St. Adomnán’s Vita Columbae (in English, Life of Columba) is a fascinating Gaelic chronicle of the life of St. Columba. He was a 6th century abbot, also of Ireland, who spent much of his life trying to convert the Iron Age Picts to Christianity, and who, like Adomnán, was an abbot of Iona. In 563, Columba sailed to Scotland, and two years later happened to visit Loch Ness – while traveling with a number of comrades to meet with King Brude of the Picts. It turned out to be an amazing and notable experience, as Vita Columbae most assuredly demonstrates. Adomnán began his story thus: “…when the blessed man was staying for some days in the province of the Picts, he found it necessary to cross the river Ness; and, when he came to the bank thereof, he sees some of the inhabitants burying a poor unfortunate little fellow, whom, as those who were burying him themselves reported, some water monster had a little before snatched at as he was swimming, and bitten with a most savage bite, and whose hapless corpse some men who came in a boat to give assistance, though too late, caught hold of by putting out hooks.”

St. Adomnán’s Vita Columbae (in English, Life of Columba) is a fascinating Gaelic chronicle of the life of St. Columba. He was a 6th century abbot, also of Ireland, who spent much of his life trying to convert the Iron Age Picts to Christianity, and who, like Adomnán, was an abbot of Iona. In 563, Columba sailed to Scotland, and two years later happened to visit Loch Ness – while traveling with a number of comrades to meet with King Brude of the Picts. It turned out to be an amazing and notable experience, as Vita Columbae most assuredly demonstrates. Adomnán began his story thus: “…when the blessed man was staying for some days in the province of the Picts, he found it necessary to cross the river Ness; and, when he came to the bank thereof, he sees some of the inhabitants burying a poor unfortunate little fellow, whom, as those who were burying him themselves reported, some water monster had a little before snatched at as he was swimming, and bitten with a most savage bite, and whose hapless corpse some men who came in a boat to give assistance, though too late, caught hold of by putting out hooks.”

If the words of Adomnán are not exaggeration or distortion, then not only was this particular case the earliest on record, it’s also one of the very few reports we have in which one of the creatures violently attacked and killed a human being. Adomnán continued that St. Columba ordered one of his colleagues – a man named Lugne Mocumin – to take to the River Ness, swim across it, pick up a boat attached to a cable on the opposite bank, and bring it back. Mocumin did as St. Columba requested: he took to the cold waters. Or, more correctly, to the lair of the deadly beasts. Evidently, the monster was far from satisfied with taking the life of just one poor soul. As Mocumin swam the river, a terrible thing ominously rose to the surface, with an ear-splitting roar and with its huge mouth open wide. St. Columba’s party was thrown into a state of collective fear as the monster quickly headed in the direction of Mocumin, who suddenly found himself swimming for his very life. Fortunately, the legendary saint was able to save the day – and save Mocumin, too. He quickly raised his arms into the air, made a cross out of them, called on the power of God to help, and thundered at the monster to leave Mocumin alone and be gone. Amazingly, the monster did exactly that.

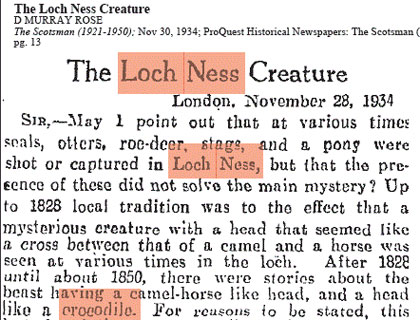

The next report of a Nessie dates from around 900 years later, specifically in the early 16th century: 1520. It should be stressed this does not mean there was a complete absence of encounters in the intervening years. It suggests that, possibly, no one chose to speak about what they may have seen. Or, more likely, if the details of sightings were passed down orally, and amongst close-knit communities close to the loch, they may have become forgotten and lost to the fog of time. As for the 1520 case – also the second case ever reported – the details came from a man named David Murray Rose, a respected antiquarian who was particularly active from the late 1800s to the 1930s. It was in 1933, when Nessie mania was in full-swing, that Rose contacted the Scotsman newspaper about his knowledge of an early episode of the Nessie variety. In a letter of October 20, 1933, Rose stated that post-St. Columba, the next reference to the presence of strange creatures in Loch Ness harked back to 1520. He cited as his source an old manuscript that was filled with tales of all-manner of strange and legendary creatures, such as fire-breathing dragons and ghostly hell-hounds.

The next report of a Nessie dates from around 900 years later, specifically in the early 16th century: 1520. It should be stressed this does not mean there was a complete absence of encounters in the intervening years. It suggests that, possibly, no one chose to speak about what they may have seen. Or, more likely, if the details of sightings were passed down orally, and amongst close-knit communities close to the loch, they may have become forgotten and lost to the fog of time. As for the 1520 case – also the second case ever reported – the details came from a man named David Murray Rose, a respected antiquarian who was particularly active from the late 1800s to the 1930s. It was in 1933, when Nessie mania was in full-swing, that Rose contacted the Scotsman newspaper about his knowledge of an early episode of the Nessie variety. In a letter of October 20, 1933, Rose stated that post-St. Columba, the next reference to the presence of strange creatures in Loch Ness harked back to 1520. He cited as his source an old manuscript that was filled with tales of all-manner of strange and legendary creatures, such as fire-breathing dragons and ghostly hell-hounds.

LOCH NESS MONSTER

LOCH NESS MONSTER

Reclaiming the Loch Ness Monster from the current tide of debunking and scepticism. If you believe there is some…

MU*

According to Rose’s research, the book in question described how one Fraser of Glenvackie slaughtered just such a dragon – in fact, what was said to be the very last Scottish dragon – but not before the beast managed to scorch much of the landscape. Interestingly, Rose said that the author of the book made a comment to the effect that although the dragon was slain, the creature of Loch Ness lived on. While Rose’s account is unfortunately brief, it does demonstrate that more than five hundred years ago there existed a tradition of monstrous animals in Loch Ness and long before the term, Nessie, was coined.