1870: The Mysterious Murder of One of New York’s Wealthiest Jews

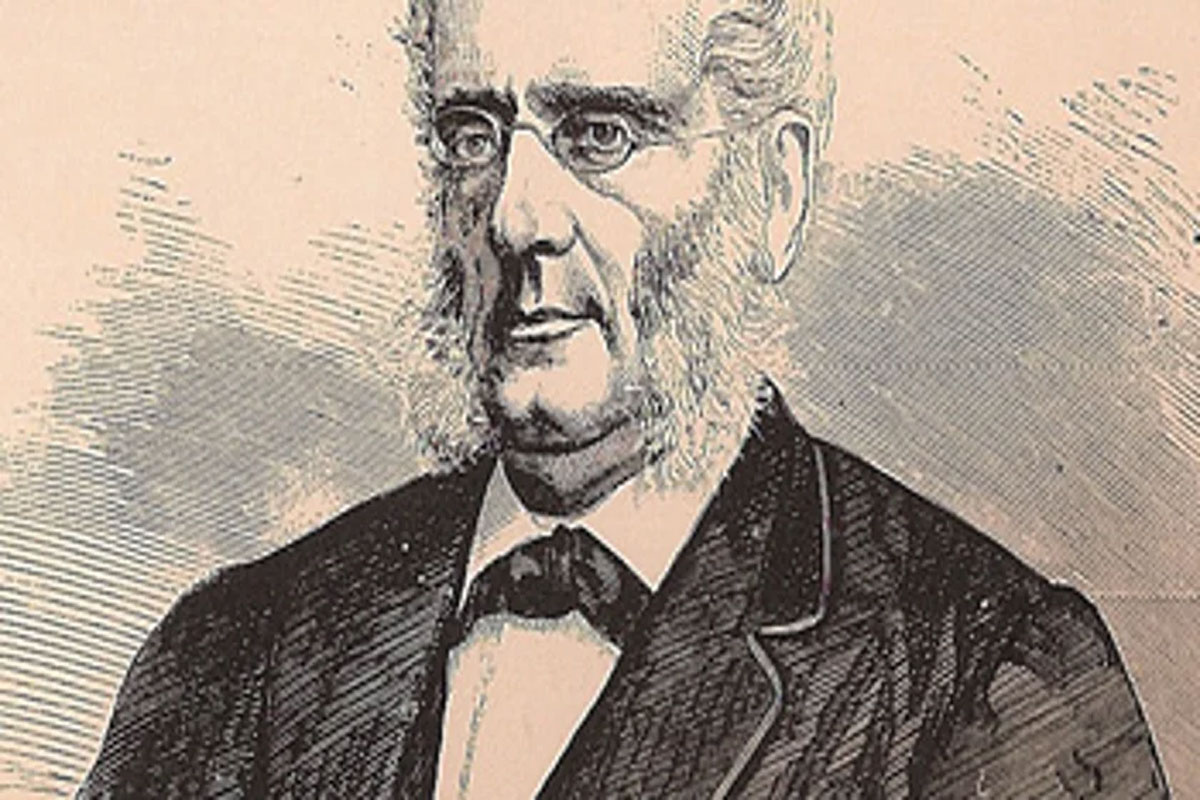

Benjamin Nathan, a scion of New York’s eminent Sephardic clan, was bludgeoned to death in his Manhattan townhouse. More than a century on, the murder remains unsolved.

Nathan’s son, Washington, as well as his personal servant William Kelly have been accused of murdering him.Credit: Reproduction

David B. Green – Haaretz

David B. Green – Breaking news, features and analyses from Israel, the Middle East and the Jewish World Haaretz

On the night between July 28 and 29, 1870, the New York investor and prominent Jewish citizen Benjamin Nathan was murdered brutally in his Manhattan mansion, at age 57. One hundred and fifty years later, the crime remains unsolved.

On the night between July 28 and 29, 1870, the New York investor and prominent Jewish citizen Benjamin Nathan was murdered brutally in his Manhattan mansion, at age 57. One hundred and fifty years later, the crime remains unsolved.

Benjamin Nathan, born December 20, 1813, was a scion of one of New York’s oldest Jewish clans, Sephardim who had come to the New World by way of England, and had a tendency to marry others from the same clan. Benjamin’s father, Seixas Nathan, was among the founders of the New York Stock Exchange, and was active in a variety of social causes in the city.

As Josh Nathan-Kazis, himself a descendant of the Nathan family, wrote in a long article about the murder in Tablet magazine in 2010, patrician Sephardi families like the Nathans “were seen as less Jewish than their coreligionists” who had arrived more recently from Germany and Russia.

“The outcome of this bit of assimilationist jujitsu,” he continued, “was that Benjamin Nathan was able to serve as president of Shearith Israel, the city’s old Sephardic synagogue, and of Mt. Sinai Hospital, originally known as the Jews’ Hospital, while also being a member of the Union Club and the St. Nicholas Society, an organization for New Yorkers of Dutch ancestry whose forebears arrived in the city before 1785.”

In an obituary for Nathan, the local business paper The Albion a paid him the compliment of characterizing him as a Jew who “might easily have been mistaken for a Christian.”

Benjamin Nathan became a vice-president of the NYSE, and invested in railroads and municipal transit lines. He had been chief aide to Hamilton Fish, later the U.S. secretary of state, during the latter’s brief service as governor of New York, and, as noted, was deeply involved in Jewish affairs.

The summer of his murder, Nathan, who had eight children with his wife Emily (nee Hendricks), had rented a 45-acre estate in Morristown, New Jersey, which was serving as their principal residence. However, that Saturday, July 30, was the anniversary of his mother’s death, and Nathan wanted to be able to observe it at his synagogue. For that reason, he remained in Manhattan after work on July 28, and planned to sleep at his residence at 12 W. 23rd Street. There, just off of Fifth Avenue, he owned a four-story mansion that was one of the grandest in the city.

After attending evening services with his sons Frederick, 26, and Washington, 22, who then accompanied him on a visit to his sister, Benjamin Nathan returned home. Because the house was undergoing renovations at the time, Nathan’s servants prepared a makeshift bed for him with four mattresses in a reception room on the second floor. Both sons came home only much later that night.

The following morning, just before 6 A.M., Washington Nathan, a handsome but dissolute young man who had spent much of the preceding evening drunk and in the company of a prostitute, checked in on his father. When Frederick heard Washington scream, he ran into the room where their father was sleeping, and found the body of Benjamin, in a pool of blood. The two shocked brothers ran out of the house, calling for help.

When the police arrived, they found that Benjamin Nathans’ skull had been bludgeoned – hit with a long iron bar a total of six times.

An initial theory of the murder saw it as a burglary gone very badly. But the theory had many holes, most obviously the fact that none of the servants in the house, nor either of the sons, had heard any kind of commotion during the night. Suspicion also fell briefly on Washington Nathan, and, more significantly, on two servants, Ann Kelly and her son William. The police questioning of William Kelly was sufficiently harsh that the Brooklyn Daily Eagle complained that, whereas the sons of the Jewish victim were treated with “tenderness [and] courtesy,” the young Irish-Catholic William was “by interrogatories accused of bastardy, burglary, theft, bounty-jumping, perjury, vagrancy, fornication and murder.”

In his article, Josh Nathan-Kazis, depending in part on a 1924 account of the killing, “Studies in Murder” by Edmund Pearson, notes that Washington Nathan had little reason to kill his father. Benjamin was worried by his son’s irresponsible behavior and had written a will that would have given Washington minimal access to his inheritance while his mother remained alive. In life, however, Benjamin was quite generous with his son.

Nonetheless, there is evidence that the investigation into the murder, in particular to the possibility that it was committed by Washington, was impeded by Benjamin Nathan’s brother-in-law, Albert Cardozo. At the time, Cardozo was a judge in the New York Supreme Court and a member of the Tammany Society, the political ring that largely ran New York in those years, while enriching itself in the process. Nathan-Kazis suggests that simple politics drove Cardozo to go to lengths to keep the family’s name – specifically that of Washington Nathan – out of any scandal, and so he saw to it that the son of the murder victim was not properly investigated.

Albert Cardozo himself was implicated in a judicial corruption scandal a short time later, and had to resign his seat on the bench. Despite his own questionable character, Albert was the father of Benjamin Cardozo, who served as a U.S. Supreme Court justice in the 1930s. He was named for his uncle Benjamin Nathan.

Washington Nathan never did recover from his father’s murder, and from the suspicion that had been cast upon him. He eventually inherited a large fortune, but he spent it on gambling and booze. He married and moved to Europe, but never settled down. Just weeks before his death, in 1892, he gave an interview to the Chicago Tribune in which he complained about how “No blood could ever be found on any of my clothes, yet people say that I killed him. My poor father! My poor father!”

Washington Nathan died on July 25, 1892. He had been in poor health for some time, and died while walking along the beach, in Boulogne, France. The death of his father, however, remains unexplained to this day.